Handwritten Math

to LaTeX

Messy Handwritting

Have you ever been sitting in on a lecture, trying to understand what is going on, focussing very hard on the derivation the lecturer is speeding through in record time. Meanwhile, you're blindly scribbling down what looks like to be chicken scratches, but in reality is a elegant proof.

You look back at your notes and now the process of cracking the enigma begins. You say to youself, 'I wish my notes looked like those nice typed up math documents. At least then I could read my own notes.' And suddenly, an idea pops into your head.

What is LaTeX?

LaTeX is a piece of typsetting software widely used in academia. Think of it as Word or Google Docs, but much more powerful because you can typeset math and format page layouts. It is relatively simple to use, after a bit of learning curve, and works by calling various commands as you type.

For example if I wanted to write out an integral problem and commentate on it, I could write something like

in LaTeX, which would produce the following document:

LaTeX... Translator?

The probelm with LaTeX, at least for most people, is that it takes a lot more time and effort to write notes in the moment using LaTeX than if you were taking regular handwritten notes. What if I could build something that could deceifer my poor handwritting and produce the corresponding LaTeX code for me?

Well, that's the plan.

Hunt for Data

Finding data for this project was a challenge in itself. There are not many handwritten math datasets that exist, at least none that I could find easily. Moreover, I needed these images to also have labels. I did not want to sift through hundreds of thousands of images and manually label with LaTeX.

Fortunately, I came across CROHME—the Competition on Recognition of Online Handwritten Mathematical Expressions—which provided .inkML to its participants. These files contained stroke data, as well as the original images and LaTeX ground truth labels. A script was written to scrape these files and extract the needed (example, label) pairs. The set of labels were standardized using an open source parser to account for equivilant expressions, and a vocabulary for the following model was created.

A Related Task

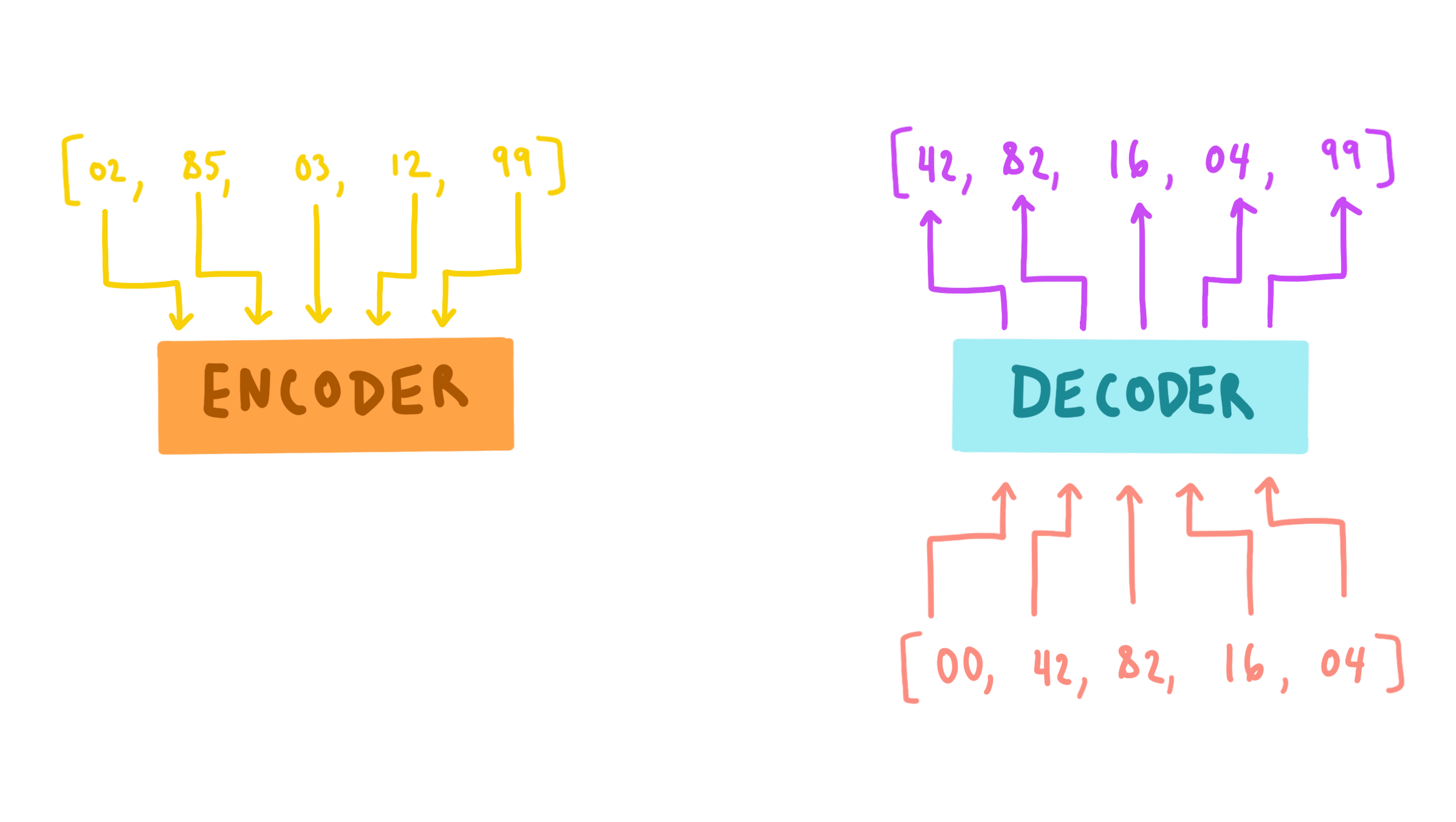

The very core task of this project is a translation task. Not exactly your typical language to language translation, but a similar idea. These traditional tasks are termed sequence to sequence translations; like translating French to English. Deep learning techniques employ an encoder-decoder structure to encode the input sequence into some internal representation, then decode that representation into the target sequence. These models are called Seq2Seq models.

Models don't really work well with words and sentences. After all, models are mathematical functions and training is nothing but an optimization of this function. So how do we rectify this? Just map the words to numbers; a process called tokenization. We see above that 'noir' is being mapped to the number 12. In practice, we don't actually tokenize words, but rather word fragments. If you tokenized on words, you'd run into issues if you encounter a word you've never seen before. But if our tokens are based on common word fragments, then you can group these together to encode a much wider range of words, building tokenizations for words you've never seen before.

The Task at Hand

With handwritten text to LaTeX, we add two extra layers of nuance compared to traditional translation.

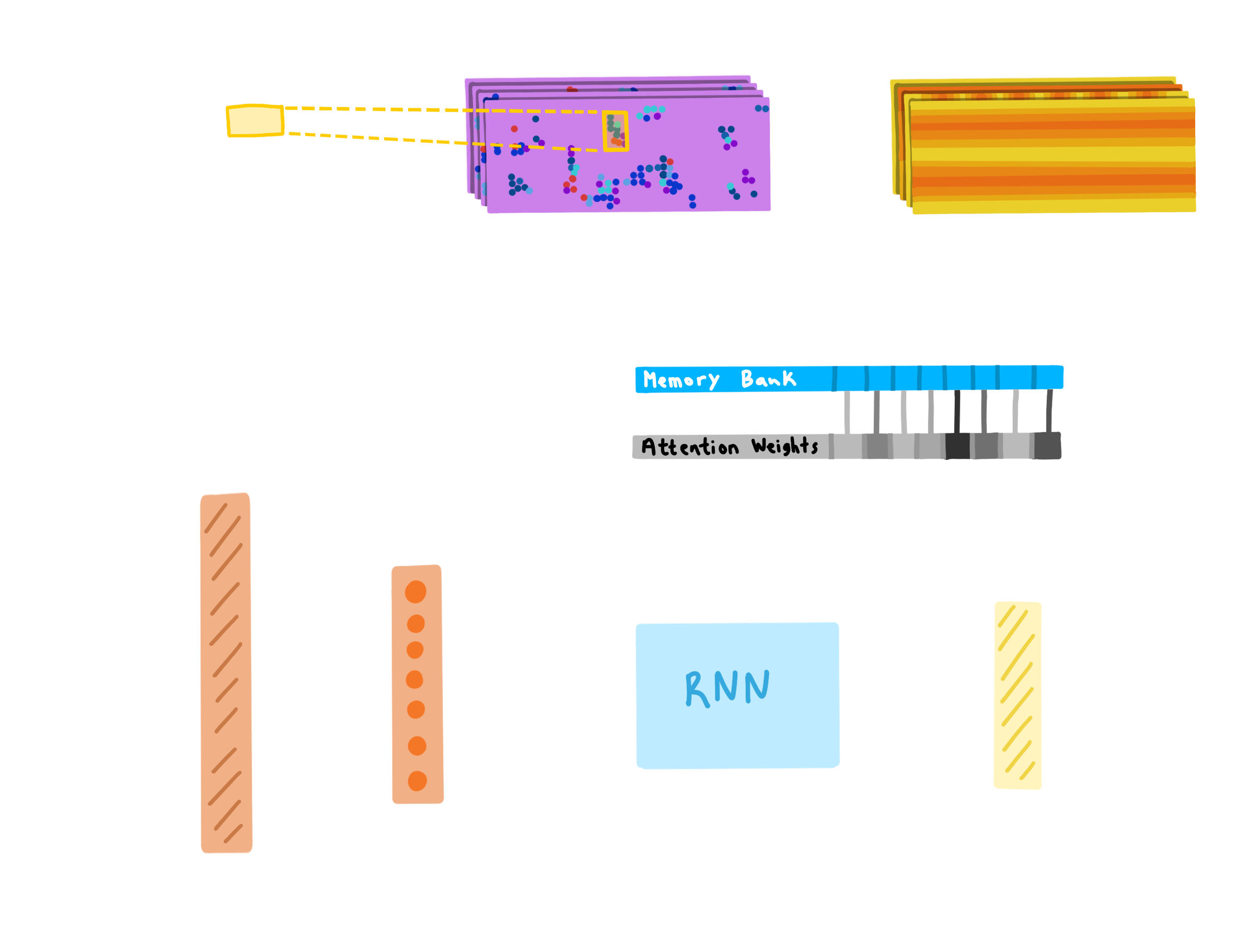

The first being that our input is an image, not a string of text. The image shows text, but is not text itself. Our encoder then must first 'read' our handwriting, make out what the handwriting is actually saying, and create a context vector that encodes all of the information it has learned from the image. There's no 'input language' tokenization because of this. We'll use a convolutional network architecture found in the literature to perform this task.

Some have coined the term Im2Seq to refer to this type of model.

The second bit of complexity comes from the fact that math as a 'language' has two dimensional spatial dependencies. For instance, two variables next to one another usually indicates a multiplicative operation. But if one is raised midway above the other, it could mean to exponentiate instead. This is different from natural language where dependencies are contrained to one dimension, forwards and backwards. With math, we add two more directions, up and down.

The Architecture

With a CNN handling the computer vision part, it should just see the equation and know what it is right?

We're done? Well, sort of. Actually no, not really. Not at all.

CNNs are good at recognition. They can make out what's present in a photo very easily, but not neccesarily where. CNNs have a property called spatial invariance, making them insensitive to the position of, for example, the handwritten integral sign in the photo. As you progress deeper in the network layers, spatial information is lost, but semantic information is gained. Ideally, we'd like both semantic and spatial information so we'll be able to learn the rules of math and how those work together to map to LaTeX commands. For instance, if two numbers appear on top of one another and are seperated by a line we'd invoke \frac{1}{2}.

To faciliate this, we'll add a two dimensional positional encoding to the CNN's extracted feature maps, similar to what Wang and Liu have done in the paper linked below. Now, we can flatten the result into our context vector and feed that into a traditional seq2seq decoder.

Naively Training

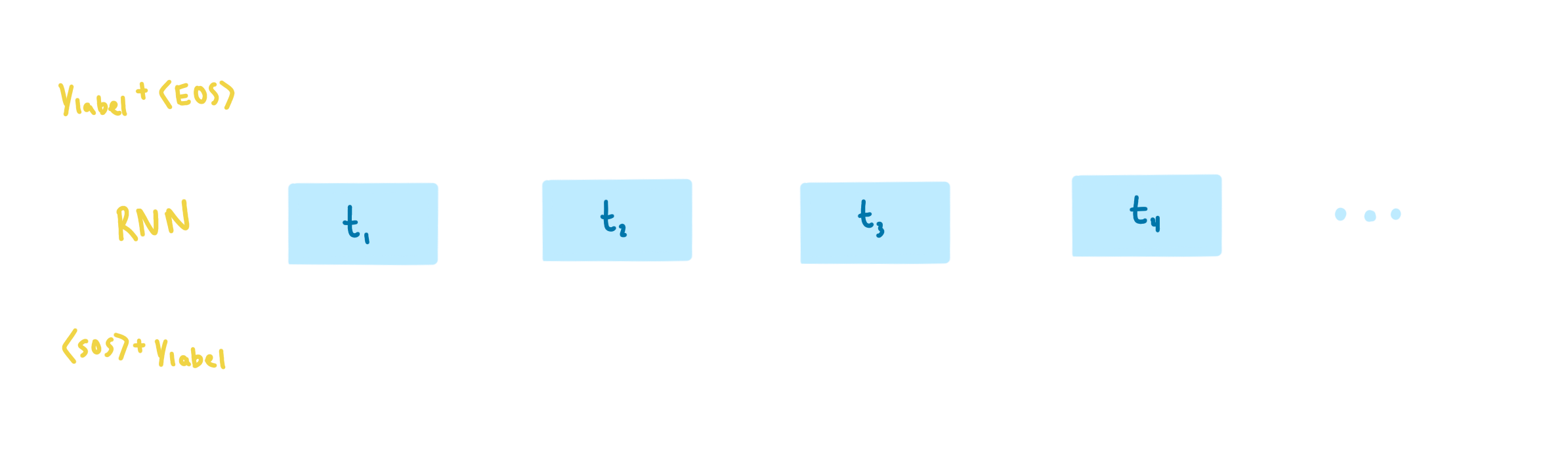

Training is carried out in the same way a traditional seq2seq model would be trained, the main difference being how the context vector is created, as described above. After we've created the context for each training example, the RNN in our decoder is passed the tokenized target one token at a time. The RNN uses attention and the context to make its next-token prediction which is evaluated through a cross-entropy loss function. At the next timestep, the next true target token is passed to the RNN, and so on. This process is called teacher forcing.

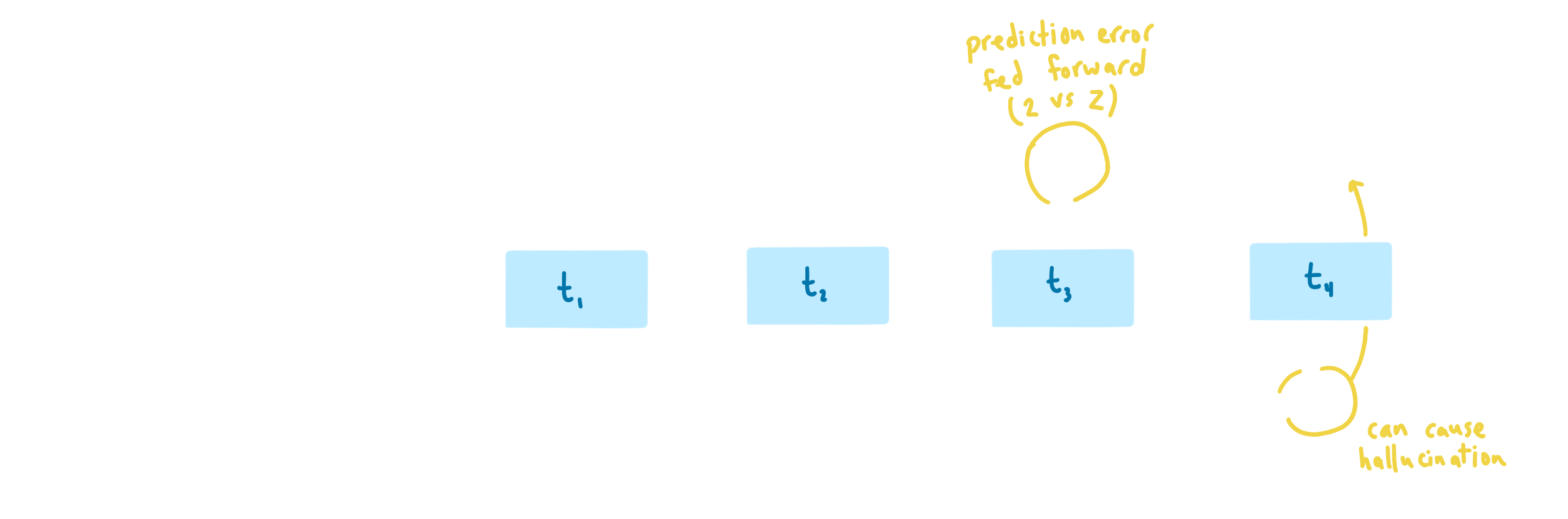

Teacher forcing is great from a compute perspective, since it accelerates convergence during training. But it introduces a pretty big problem in our use case.

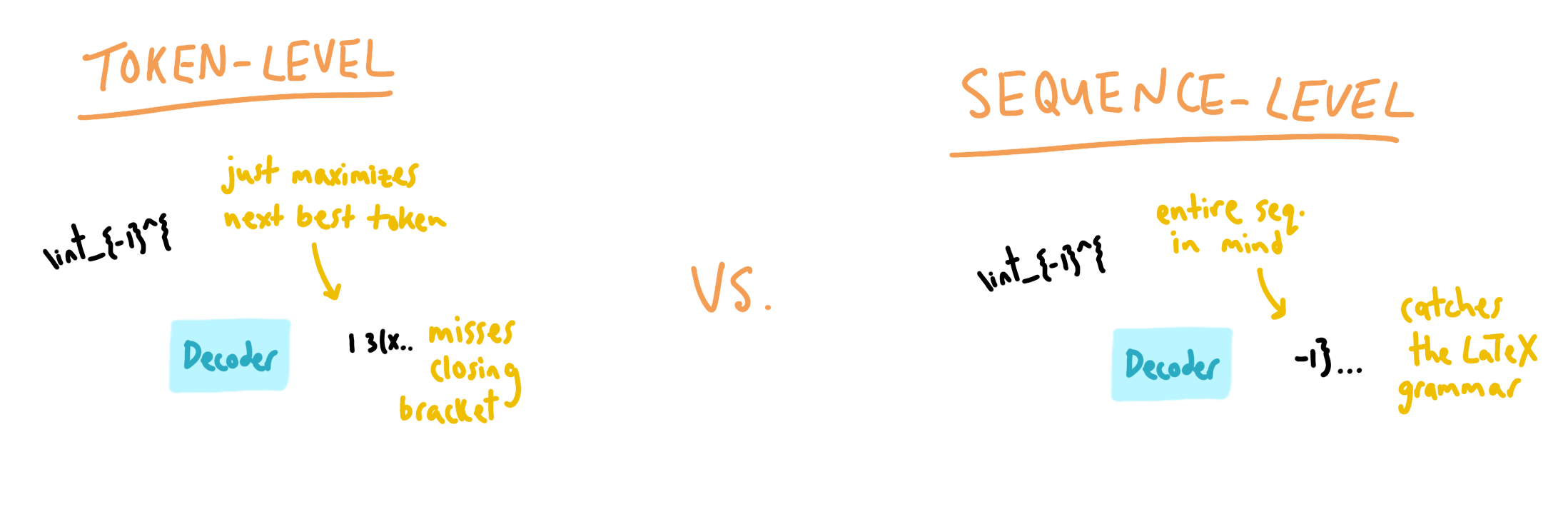

When using the model in inference mode, we no longer have a ground truth label to feed the model. The model uses the context to make a prediction, and then that prediction is cycled back in until the end of the sequence. You see, there is a discrepancy between how the model was trained, and how the model is used. This is known as exposure bias. Cross entropy loss maximizes the probability of the next correct token, without considering the sequence-level context governed by LaTeX grammar

Sequence-level Training

The exposure bias issue arises because cross-entropy is a token-level loss function. What if we had a different objective function? One that took into account the entire sequence, eliminating exposure bias?

Enter BLEU score loss.

BLEU score is a metric that quantifies 'how good' a single machine-translated segment is comapared to if a human were to do it. In traditional translation, these segments are typically sentences, but in our case we have chunks of LaTeX code. Scores are calculated for translated chunks by comparing them with a set of good quality reference translations. These scores are then averaged over the whole corpus to reach an estimate of the translation's overall quality. BLEU is inexpensive to compute and was one of the first metrics to show a high correlation with human judgements of quality.

With this sequence-level loss, we can optimize the prediction of individual tokens within the context of the entire sequence. It also eliminates the exposure bias problem because the optimization is no longer based on each individual token, but on the entire sequence. All is well! Well, there are a couple of logistical issues. Using a sequence-level objective to train from a randomly initialized model state is computationally infeasible. Instead, we first train on a token-level objective, then use that as a starting point for sequence level training.

But, there is still one more problem. BLEU loss is not differentiable.

Reinforcement Learning?

To address this problem, some solutions have been proposed in NLP community that propose to formulate the optimization problem as a reinforcement learning one.

In this setting, the prediction model is treated as an agent. Prediction on the next token is an action. At completion of the prediction, the predicted sequence is compared against the ground truth sequence to get a sequence level evaluation score, which is the reward. The parameters of the neural network define a policy. Even though BLEU is not differentiable, the policy gradient algorithm can be used to transform the gradient of expectation as an expectation of gradient so that we can avoid taking derivative over the BLEU 'reward' function.

Next Steps

Unfortunately, this is much easier said than done. My experience with reinforcement learning is limited compared to other areas of machine learning. This step has proven to be a tall hurtle and I am determined to clear it... at some point. The state of this project is currently on hold as free time has dwindled down. If someone reading this just so happens to be a reinforcement learning expert or perhaps you have an alternative idea on how to proceed, please reach out to me!

Links to my socials can be found under the contact page. A link to the the current code base for this project can found at the top of this page under the main title.

References

• Z. Wang, J. Liu, 'Translating Math Formula Images to LaTeX Sequences Using Deep Neural Networks with Sequence-level Training,' arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.11415, 2019.

• S. Shen et al., 'Minimum risk training for neural machine translation,' arXiv preprint arXiv:1512.02433, 2015.

• L. Wu, F. Tian, T. Qin, J. Lai, and T.-Y. Liu, 'A study of reinforcement learning for neural machine translation,' arXiv preprint arXiv:1808.08866, 2018.